I start this latest ‘In Love With’ article with three disclaimers. Firstly, I am not claiming to be an expert in kaiju films or even particularly knowledgeable; I’ve seen a few, but interest was only ever part of a greater love of Asian cinema. There are some great articles online and plenty of fine YouTube videos that give a much more detailed examination of the cultural icon – mine is more of a tip of the hat to the 1954 original and its impact. Secondly, I am shamelessly writing this article now to piggyback on the success of ‘Godzilla Minus One’, though hopefully it is more than just some inept bandwagon jumping. Finally, this isn’t some weird article where I claim to be in love with the beloved Japanese monster in a literal sense; my regard for him is purely platonic.

As mentioned, this article is focused on the original Ishiro Honda film which I rewatched yesterday in preparation for watching ‘Godzilla Minus One’ at the local cinema. In so doing, it was a reminder of how skilful filmmaking can be and how, especially in the West, that element of subtlety has been lost, perhaps never to return. Of course, if Honda had access to the technology we have today, it wouldn’t necessarily have been to the detriment of the original. Nevertheless, the restrictions that available effects placed on filmmakers at the time required a little more savvy, especially in the first film.

‘Godzilla’ gives a nod to the atomic age creature features being released in Hollywood at the time, especially ‘The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms’, yet it fully utilises Japan’s very unique perspective on the concept. The horror of events that took place less than a decade earlier in Hiroshima and Nagasaki are seared onto the celluloid throughout as is the commentary on atomic weapons.*

*Every nation could legitimately make a film about the horrors of World War II, some with more justification than others, but only Japan could comment on what would be the weapon that would dominate the future.

‘Godzilla’ is a bit of a victim of its own success. Like many films that have gone from being just works of cinema to cultural milestones, there is a tendency for the original work to be either distorted by revisionism or parody. I always think of ‘Rocky, ‘First Blood’ and ‘Saturday Night Fever’, gritty films that have been lost in the cultural significance that followed, and become works that everyone has seen, but few have actually seen. These are the movies that everyone can reference and usually add some ironic wink at their apparent cheesiness, but forget that these are truly excellent films. ‘Godzilla’ belongs in that category. It’s not helped, of course, by the deluge of sequels and spin-offs that followed; these undoubtedly added to the mythos and expanded the kaiju pantheon, but bear little resemblance to the original. Not that we cannot enjoy ‘Destroy All Monsters’, but the original ‘Godzilla’ deserves special scrutiny.

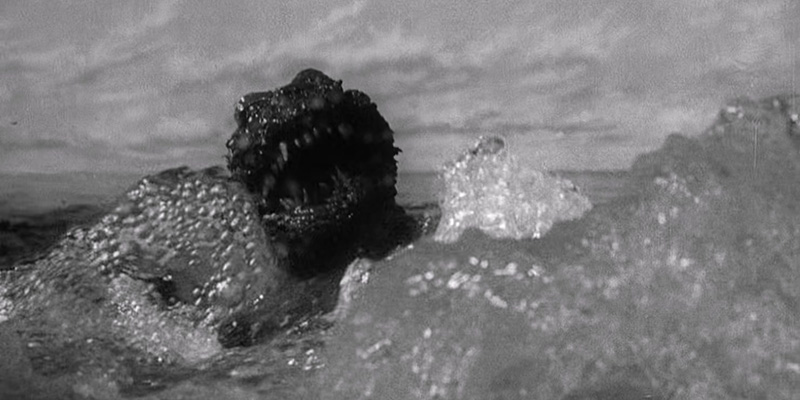

The first thing that strikes you about ‘Godzilla’, and something that is often found in great horror films of the era, is how little the titular creature is seen. There is a brief flash early on, escalating to a full reveal later on, but so much of the work is about atmosphere, that forgotten cinematic trick. While filmmakers today are keen to show their hand immediately, ‘Godzilla’ proceeds with nothing more than a quick image and the ominous ‘thud’ of his movement. This is tremendously effective, especially when the aforementioned ‘thud’ rocks the house and trees (and resonates quite effectively through a good home cinema set up!). The conclusion of this technique is when his stomping, thudding walk shakes down sea-front houses on Odo island. It’s a great scene, one of the most effective of the whole film and sets up Godzilla as the terrifying monster you expect him to be.

‘Godzilla’ is also a very talky monster movie. And that’s a good thing. Rather than titanic battles between monsters, it’s a story told from a human angle, something that immerses you in the action. While later films often side-lined the human element and became more like Japanese Wrestlemanias between a rich catalogue of creatures, this is about how people would react to events. Honda takes it seriously and because of this, the sense of dread works as much as any scene of wholesale destruction. The thing with the latter is that the effects will inevitably look aged after nearly seventy years; that’s not to say that they are distracting for the era, but there’s no question that occasional man-in-rubber suit stomping and model work becomes a bit too obvious. Yet that oppressive waiting for Godzilla to re-emerge…that is priceless.

An aspect of ‘Godzilla’ and, indeed, many older disaster films is that they highlight the aftermath of attacks. Now we aren’t expecting harrowing scenes of mutilated bodies and overfull hospitals in today’s 12A disaster films, but there is a cold precision that just wipes secondary characters away without suggesting that they are important. You see cities destroyed but as long as the main players are ok, you are meant to merely let it wash over you. I remember watching, for my sins, ‘2012’, where John Cusack and his kids are weaving in-and-out of skyscrapers that are falling – and killing thousands. But, hey, it’s all right, the main family is going to be ok so just switch off from the mass destruction. Personally, I find that this alienates me very quickly and is a reason why something like 1974’s ‘Earthquake’ will always have more resonance to me than modern blockbusters. ‘Godzilla’ shows the aftermath in chilling detail; victims stretchered away, conflagrations everywhere and people looking lost. It truly conveys the drama of the situation, far better than computer effects ever can. It’s surprising how grim the whole look of the events are – we’re not talking ‘The Road’, but it still packs a punch.

The final part of the 1954 Godzilla – and perhaps the most unique to the time – is the atomic weapon allegory. It would be touched on in many monster films that followed, but occurring so close after Hiroshima and Nagasaki gives it a gut-punch power. It also reinforces the moral dilemma of the later decision to use the ‘Oxygen Destroyer’ – its creator, Serizawa has that Oppenheimer look in his eyes as he realises that saving the immediate future might massively endanger the world further forward. It’s a brave move and, remarkably, it’s done without heavy-handed moral judgements, something which might have been easy from a Japanese perspective considering their experiences in 1945. ‘Godzilla’ understands that allegory doesn’t have to overtly point fingers at one nation or another but can offer food for thought instead. It’s not about casting real or imagined human villains, but more about showing how events inevitably affect innocent civilians of all sides.

As a kaiju film, the original ‘Godzilla’ might be a tad austere for some. However, its subtlety is what really impressed me. Yes, it is still a guy in a rubber suit stomping on Tokyo, but it is much more than that. Later efforts were fun and continue to be so, but Honda’s original work is quite special. It might be forgotten because everyone’s favourite giant lizard is so entwined in the cultural zeitgeist. But, with the great success of ‘Godzilla Minus One’, it’s well worth revisiting.

- In Love With… One-Armed Swordsman - March 3, 2025

- In Love With… Enter the Clones of Bruce - November 25, 2024

- Two Toothful Tigers – Farewell to Lee Hoi-Sang and Norman Chui - September 22, 2024