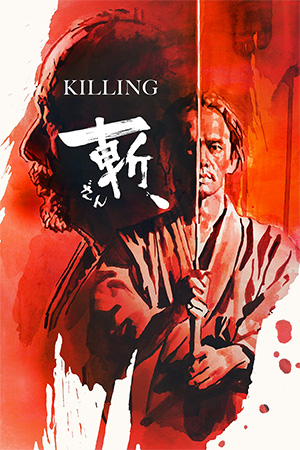

‘Killing’, is Shinya Tsukamoto’s revisionist samurai film from 2018, a clear thematic successor to his anti-war epic, ‘Fires on the Plane’. Here the classical samurai genre, a staple of Japan’s cinematic heritage, meets a fiercely independent voice, a filmmaker who defies classicalism in favour of radicalism. Thematically the film is a juxtaposition of artistic expression before it even begins, because both the genre and the director are loaded with such opposing symbolism. Old meets new, but with such high levels of expectation, can ‘Killing’ ultimately live up to the demand? Can Tsukamoto prove that he has something to say in an already saturated discourse. Yes. Yes, he can.

The story centres around Mokunoshin (Sosuke Ikematsu), a young but well-trained samurai that has found refuge in a small rural farming village. Without a leader, the warrior has no real motive, until he meets Sawamura (Shinya Tsukamoto). This veteran samurai wishes to recruit Mokunoshin, to which he agrees. All is well, until a rogue gang starts causing trouble in the farming village, leading Sawamura to soon learn that Mokunoshin has never killed anybody, and more importantly, seems to lack any aggression to do so. The narrative spirals out of control from here, resulting in trademark levels of chaos and violence.

The film takes the genre to a place of reflectivity, the code of honour that surrounds the mythical warriors is conflicted with their inevitability to use violence. The zen qualities that often get applied to samurai are questioned, Tsukamoto suggests that passivity and peace will always be antagonised when aggression is so strongly associated with it. An idea that feels universally relevant, as images of peace are always shown with victorious militaries leaving a war-torn country. We live in a vizard of peace where secret/pseudo wars are fought in far away countries and every world leader seems seconds away from pressing a button. Countries suggest we live in peace, yet they all need nuclear weapons to uphold it. ‘Killing’ questions this, it looks at why peace and violence are so mutually related, and it ultimately concludes that violence is always the predominant force. Ironically, the two fail to coexist peacefully.

The film reveals all of this through an intimate story, a small cast, a small setting, even the crew is tiny with Tsukamoto taking on the role of director, actor, editor, writer, and cinematographer. It feels far removed from any outsider influences, everyone involved seems to be there because they believe in it, making it transcend its clear budgetary constraints. All spectacle is removed in favour of story and characters, but it does feel limited. Its obvious that the budget has made the film smaller than it maybe first envisioned, and while it still calves an incredible story from so little, one cannot help but feel it wanted to say more than its budget allowed. A clear result of Tsukamoto’s commitment to staying separate from studio interference, and thus, a forgivable and understandable downside to what is still a powerful piece of cinema. And as aforementioned, something that is overcome by everyone having a clear belief in the project.

Overall, ‘Killing’ is a definitive example of why the samurai genre is so universally recognised as a majorly important genre. Its national iconography transcends Japan with thematic ideas that are internationally recognised. Tsukamoto proves that he can stand with the filmic legends as he proudly represents a unique sense of style in a densely populated medium. The film shows maturity and reflectiveness while upholding the ‘edginess’ that helped define Japan’s Iron Man. ‘Killing’ is a must watch for any fan of his work, or for anyone looking to explore his filmography, it’s a great place to start.