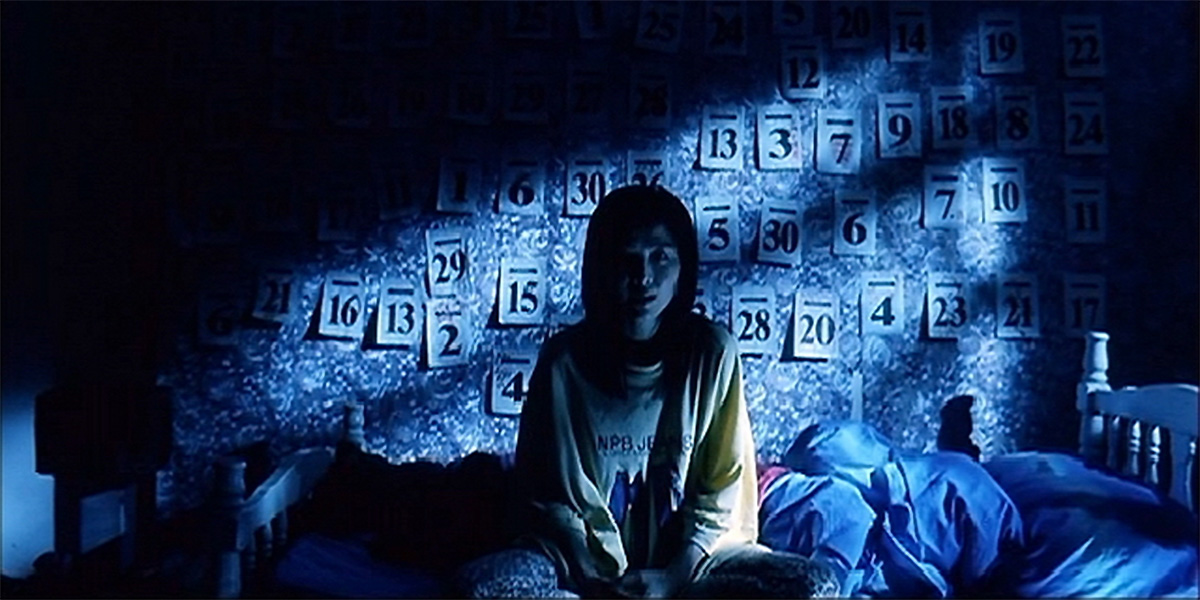

A suicide pact between terminal cancer patient Yau Yin Ping (Winnie Leung) and her boyfriend Jack (Marco Lok) is unexpectedly curtailed when young police officer Sum Ka Lok (Bernard Chow) happens across their unconscious bodies. By sheer coincidence Lok shares the same rare blood-type as the tragic lovers and, along with fellow donors Joy Yip (Niki Chow) and Eric So (Cyrus Chow), supplies the life-saving means of transfusions for the couple. While Jack is saved, immediately falling into a coma, Yau is not so fortunate. Within hours of their selfless act the three Good Samaritans find themselves besieged by horrifying visions of the freshly deceased Yau.

Architect So is overwhelmed by his visions, encountering the grotesque phantom everywhere he turns as well as being swamped by premonitions of his own suicide. For Joy, who has long suffered from psychiatric disorders following a nervous breakdown triggered by her mother’s (Chiu Yue Ming) murder of her father, the haunting pushes her back into a state of emotional and psychological detachment. Soon the message becomes clear for the three donors: Yau’s spirit is pushing them to murder the comatose Jack so that he might join her in the afterlife. Once bodies start piling up around the three, Yau’s vengeful soul forces them towards committing the unthinkable.

Having toiled away in the industry as an assistant director since the early nineties, inclusive of work on Ringo Lam’s ‘The Adventurers’ (1995), Daniel Lee’s ‘Black Mask’ (1996) and an unexpected stint on Aman Chang’s ‘Sex and Zen III’ (1998), Soi Cheang diverged from the mainstream at the tail end of the decade to mark his mark in Hong Kong’s burgeoning independent film scene. Work with B & S Productions on a handful of small digital video features led to Cheang scoring his solo breakthrough with (the relatively obscure) ‘Diamond Hill’ (2000); which in turn led back to the mainstream with an offer from Mei Ah Entertainment subsidiary Brilliant Idea Group to helm a modestly budgeted horror opus, ‘Horror Hotline…Big Head Monster’ (2001). An effective fusing of local urban legends and ‘The Blair Witch Project’ (1999), Cheang’s maiden horror venture proved a minor hit, both domestically and abroad. Quick to capitalise on the resurgent horror industry, in the wake of the enormous success throughout South East Asia of the Pang Brothers’ ‘The Eye’ (2002), Albert Yeung’s Emperor Multimedia Group identified Cheang’s inherent talent for the genre and snapped him up for the successive ‘New Blood’ (2002), a dark and sombre revisionist take on local folklore.

Written in collaboration with early Milkyway Image screenwriter Szeto Kam Yuen (‘The Longest Nite’, 1998), ‘New Blood’ draws on Chinese superstition that dictates the soul of those who suffered a violent death, or committed suicide, will linger after death to wander aimlessly unless it is guided into the afterlife within seven days of the body’s passing. It is this seven-day cycle, where the wayward soul exists in a state unaware of its mortal passing, which Cheang and Szeto utilise as the instrument of almost all the unremittingly grim horror that follows. Paramount to the whole premise working is an effective antagonist and in Winnie Leung (‘The Forbidden Legend: Sex & Chopsticks II’, 2009), buried under stark pancake makeup and grotesque contact lenses, Cheang harbours the perfect vessel to generate the necessary scares. Apart from Niki Chow (encoring from Cheang’s prior ‘Horror Hotline…Big Head Monster’, 2001) the remaining cast are largely unknowns to wider international audiences; comprising Bernard Chow, in his solo screen outing as police officer Lok, and Cyrus Chow (‘Sunshine Cops’, 1999) as architect Eric So. Against expectations, both fulfil the requirements of their roles capably and are revealed to conceal perhaps more personal demons than Leung’s omnipresent ghost.

However, what is most remarkable of Cheang’s often unrelentingly tense exercise in cinematic horror is the writing assigned Chow’s character. It’s not often (and certainly not indicative of the era) that a central part is painted in such ambiguous shades of darkness, being that Chow’s Joy Yip is defined from the outset as suffering with serious mental health issues. But instead of exploiting that aspect of the character, Cheang and Szeto cleverly involve it into the very fabric of the plot as well as treat the subject with sympathy uncommon to Hong Kong cinema. Joy’s mental illness becomes such an intrinsic element of Chow’s performance that, before proceedings ultimately come apart at the seams in the lead-up to the climax, the viewer is almost completely unaware that Cheang has harnessed that facet to execute a powerful sleight of hand. Whilst we’re all immersed in Ko Chiu Lam’s (‘Green Snake’, 1993) evocative cinematography, which brilliantly stages Cheang’s set-pieces in varying gradients of inky black shadows and white light, and assailed by Nip Kei Wing and Phyllis Cheng’s multi-channel sound design, the director plays his cards just close enough to his chest that it’s almost impossible to anticipate the finale’s bitter sting; even though it is centre-stage at all times.

Through no fault of its own, international Hong Kong cinema journalism has long existed on the misnomer that the region’s genre outings were predominantly infused with healthy doses of comedy ala Sammo Hung’s ‘Encounters of the Spooky Kind’ (1980) and Ricky Lau’s ‘Mr. Vampire’ (1985) over a more “straight-laced” approach to horror. Arguably, this has been perpetuated over the years due to the limited availability of materials and collective history in the wake of the explosion of interest in Hong Kong’s film industry that took global hold at the onset of the nineties. However, once a sizable salvage of the Shaw Brothers library became commercially available the territory’s frequent flirtations with “straight horror” have been traceable as far back as the fifties with productions akin to Li Han Hsiang’s ‘The Enchanting Shadow’ (1959). With the success of ‘The Eye’, Hong Kong simply reclaimed its long-standing crown for serious genre film and Soi Cheang’s ‘New Blood’ extrapolates spectacularly on that theme. Dark, haunting, deliberately paced and spine-tinglingly atmospheric, under Cheang’s hand ‘New Blood’ generates as many of its heart-racing episodes in total silence as it does in falling back on the clichés of the genre.

A great horror director will scare his audience as easily with a sense of unease and disquiet borne of pre-emptory moments of unsolicited (and unexpected) calm, as one given over to showy theatrics and a bombastic soundtrack designed solely to startle them from their seats. Cheang achieves that end in excess throughout ‘New Blood’s duration, delving deeply into the darkness of not only his focal haunting episodes but also the very fibre of those affected. He also skilfully plays on the deliberate ambiguity of one of his central characters, toying with perceptions of reality and knowingly misleading his viewer all the while. An oft-shocking blend of contemporary horror and traditional Chinese folklore, ‘New Blood’ is a smart, efficient and alarmingly effective genre piece that sits effortlessly alongside some of the finer horror entries of the period as an unremittingly morbid and blood-curdling exercise in unadulterated terror.

Originally published on Hong Kong Rewind © 2011, M.C. Thomason

- My Name Is Nobody - March 12, 2021

- Girl$ - December 4, 2020

- Seeding Of A Ghost - August 7, 2020