In the last years of Edo era Japan, assassin Kenshin Himura gains a reputation as the most brutally ruthless killer on the battlefield. Just as Kenshin throws himself into the final conflict – and a duel with a noted rival – peace is announced, the Meiji era begins and the armies drop their weapons. Kenshin becomes a peaceful wanderer with just an inverted blade as defence and his legend passes into folklore.

Six years pass and while travelling the country, Kenshin meets idealistic young swordswoman Kaoru who is struggling to keep her late father’s dojo open. The now anonymous ronin becomes embroiled in Kaoru’s battle to fend of the nefarious interests of an opium dealing businessman Kanryuu eager to buy her land, but remains true to his vow not to use his blade to harm or kill. The stakes are raised when chemist Megumi – the last person to know the formula for a particular refining process for the drug – seeks sanctuary with Kenshin and his new friends. With a whole army of former samurai – now reduced to starving hoodlums – at his disposal, oily villain Kanryuu pushes the pacifist resolve to the limit.

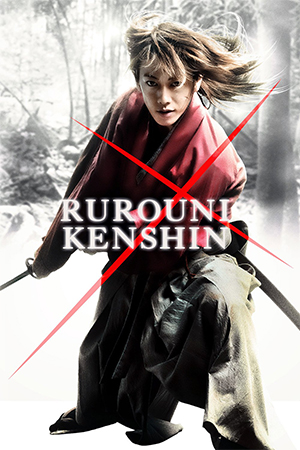

Watsuki Nobuhiro’s popular manga (which once again I must confess to not being familiar with) comes to the big screen with the first part of a trilogy (the other parts in production as I write this) and no expense is spared in making them look as slick as possible. This is a world away from the gruff, brooding samurai heroes of Mifune, Nakadai, Wakayama and Katsu; now the ronin lead character is played by young idol Takeru Satoh. And yet, despite my aged and somewhat jealous reservations on having such a ludicrously good looking star in the lead role, Satoh manages to slot nicely into the forefront. It’s the era of the silken-skinned, exotically-coiffured action hero, that much is true, but to dwell on such things and undermine Satoh’s performance would be churlish to say the least.

‘Rurouni Kenshin’ is packed with chanbara cliches – the former killer looking for redemption, the Westernised villain, the conflict between tradition and modernity, the unlikely teaming of former foes near the end etc. Nevertheless the execution of the story is handled with enough chutzpah by director Keishi Ohtomo to make the overriding sense of deja-vu less of a problem. Ohtomo clearly takes stylistic cues from his source material and makes the film pure comic book indulgence rather than attempt any sober contemplation on Japanese history. There are a few moments where other issues are touched on – the plight of the unemployed, destitute samurai is a fascinating plot thread that is teasingly hinted at. ‘Rurouni Kenshin’ is resolutely pulp entertainment though and while it is unlikely to be mentioned in the same breath as ‘Yojimbo’ in years to come, it hits enough of its targets to satisfy.